Nuclear Proliferation Among Allies in Asia is Inevitable

Unexpected change comes 'gradually, then suddenly'

This will be a dual posting with our sister publication, Thirdoffset Strategy

Washington DC 16 May 2023

When we liberate Taiwan, if Japan dares to intervene by force, even if it only deploys one soldier, one plane, and one ship, we will not only return reciprocal fire but also start a full-scale war against Japan. We will use nuclear bombs first. We will use nuclear bombs continuously until Japan declares unconditional surrender for the second time. What we want to target is Japan's ability to endure a war. A long as Japan realizes that it cannot afford to pay the price of war, it will not dare to rashly send troops to the Taiwan Strait.

China’s escalating bellicosity and the rapid scaling of its capabilities and capacity to coerce and punish at long range, has triggered wide variety of responses around the region and indeed the world. As we have previously assessed, Australia has moved to a war preparation footing; Japan has doubled its defense spending and will adopt long range fires [in tension with its constitution]; and the regional alliance system has shifted from a US centric model to a broad based network. Thirdoffset has already written about the inevitability that Australia, Japan, and possibly South Korea, will eventually acquire their own nuclear deterrents. However, those comments were only in passing. Its time to deliver a deeper explanation for this position.

This article will dig a little deeper into recent developments that suggest that allied nuclear proliferation is further advanced than we previously realized. In particular, South Korea, Australia and Japan, all appear to have (indirectly and incrementally) adjusted their policy settings.

Allied acquisition of a nuclear deterrent makes sense for two primary reasons:

It is far more cost effective than trying to meet the PLA ship for ship, plane for plane

It is also the only full guarantee of sovereignty

The proliferation considerations are immense and much can happen in the intervening years. But when push comes to shove, states will act to preserve their interests setting aside treaty obligations if necessary. It is hard to predict the timeframe for the culmination of these developments, however it may be sooner than one might imagine.

General Deterrence

Post 9/11 US deterrence policy has failed. Russia was not deterred from attacking its neighbors from 2008 onwards. Just like Hitler in the interwar years, a small test bite into Georgia turned into a huge chomp into Ukraine, and soon after an attempt to swallow Ukraine whole. Only then did the West finally act. China salami sliced its way into the South China Sea. A “holiday resort” here, a “fish processing plant” there slowly turned into a string of sea forts with military runways, hardened bunkers and long range missiles extended Chinas A2AD deep into the Pacific. Remember when China bought the “floating casino”? It’s now called the Liaoning. America just sat there and watched. Twenty years ago China’s military was weak. If America had to use force to keep the Chinese out of islands with multiple sovereignty claims it could have done so at relatively low cost. Instead, we were chasing ghosts in the Kush. The lesson for friend and foe alike was distract America and even a weak power can make highly visible strides against US interests and allies completely uncontested.

Extended deterrence

Australia, Japan and South Korea, each have a formal alliance treaty with the US. An unwritten rule of these treaties is that in exchange for not developing their own nuclear weapons, America guarantees the security of these allies against nuclear attack, by extending US nuclear deterrence to “cover” our allies - which is why its sometimes called the “nuclear umbrella”. For extended deterrence to work, it has to be credible to our allies and foes. It has always had a credibility problem. An American president is going to lose New York because someone else nuked Canberra? Really?

When the US has conventional military superiority compared to any possible aggressor, and its general deterrence policy has teeth, extended deterrence is plausible because the actual risk is a massive conventional response that could escalate to a nuclear confrontation. When US conventional capabilities, capacity and intent, are judged by allies to have eroded to parity or worse, smart allies make preparations to go it alone and/or to bandwagon with one another.2

This is exactly what Japan, Australia, South Korea (and many others) are doing.

Extended deterrence guarantees the US will launch a nuclear counterstrike against an aggressor on our allies behalf. The aggressor must believe that an attack on a US ally is in effect the same as nuking New York. If they do not believe this, they will make a calculation of what targets they can attack with nuclear weapons without US reprisal.3

If they get this wrong and the US does act on its extended deterrence obligations by counter attacking, the aggressor then has to consider if it will carry the fight to the US homeland. Any attack on the US would be intolerable to Americans (remember 9/11 was just 4 planes - look how the US reacted to that) and would inevitably result in a robust US counter strike. This is called an “an escalate to deescalate” response. The idea being that any further response would unleash a suicidal global nuclear war. Thus, having suffered a robust US nuclear strike, the aggressor would be deterred from any further nuclear use.

If you think a nuclear state [China, Russia, North Korea, India, Pakistan, the UK, France, Israel, or the US] will set aside their fury at being counter-nuked and swallow their national pride and do nothing further with the most powerful weapons at their disposal, then you find “an escalate to deescalate” counter-strike deterrence strategy credible.

There are a few more credibility challenges in extended deterrence. Let’s use a practical example. The Joint Defense Facility Pine Gap (JDFPG), is a vital node in the US global intelligence network. It is a high value military target.4

It is also in an extremely remote and hard to access location at the best of times, and especially in a war.

Located around 11 miles SW from Alice Springs (~pop 31,000), Pine Gap is nestled in a valley in the middle of the outback. Darwin (~pop. 138,000) is 940 miles to the North on a one lane in each direction road. There are no farms or rivers or settlements - it is more like the moon than it is like rural America or Europe. The outback is mostly rock, dessert, the occasional bouncing marsupial, and endless burning sun.

Low yield nuclear weapons can be employed in ways that minimize fallout. They are not the total Armageddon of the movies. A 15kt nuclear detonation on the facility would be limited to a localized effect. It would only kill the people on site - likely no more than ~1000 - with little other non-military effect because there is nothing else within the blast radius .5

There is a reason some Australians call the outback the ‘never-never’.

As such, the JDFPG presents a prime target for nuclear weapons: unreachable by conventional means, of high military value, with little to no prospect of collateral damage. Perhaps in a nod to the less than seamless coverage of the nuclear umbrella in Pine Gap’s case, its NSA cover name is reportedly RAINFALL.

Nuclear warfare is one of those things in life, like the death of a parent or a child, where you think you know how you will respond but reality is always totally different to expectations.

If you think an American president would risk New York (pop 8.8m) or LA (pop 3m) in order to respond to a single bomb dropped just on Pine Gap (pop. ~1000), then you find extended deterrence credible.6

As a former Australian defense official, Thirdoffset has never accepted that America would risk Washington DC or LA, and by extension, a civilization-ending nuclear war, in a response to a lone nuclear attack on a remote outpost like Pine Gap. Previously, that scenario was never really plausible. Despite Pine Gap being a significant node in the US network during the Cold War, a lone Russian nuclear attack was not credible. There would be no sensible reason for the Russians to strike Pine Gap without it being part of a much bigger war. In that scenario, Pine Gap would barely rate on the Russian ‘SIOP’.7

Chinese nuclear targeting and operational risk calculus

The same does not apply to China today. US dependence on space assets has encouraged the PLA to devise a wide range of counter-space options. It should be expected that a first move in a major war would aim to blind the US and its allies. The loss of satellite navigation, communications, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance would fundamentally degrade the operational effectiveness of US and allied forces and impose very high costs, fog and friction, on continued fighting.8

This stratagem elevates Pine Gap in the Chinese counter-space priority target list. A lone PLA nuclear strike on the facility looks attractive given its importance, inaccessibility to conventional weapons, remoteness (low collateral cost), and a calculated risk that the US would not in fact retaliate in kind due to overriding US sovereignty considerations, future escalation control options, and a belief that a US conventional retaliation could achieve near-nuclear effects. If it was located in downtown Sydney (pop 5m) that would be one thing. Sitting in the outback far from any civilization - it’s an ideal target.9

The same incentives apply to a nuclear strike on Guam (~pop 168,000). Being a territory and not a state (sovereignty matters), with a small population, in a remote location, and of ultimate military value. Guam is home to the only submarine maintenance facility in the pacific West of the international date line, regionally rare B52 capable runways, a critical logistics hub, one of only two navy VLS missile reloading facilities (the other in Japan - if these are lost US destroyers and submarines have to sail to Hawaii or San Diego to rearm).

A lone nuclear strike - one bomb each on the US naval base and US Air Force base - at opposite ends of the island, would leave the capital Hagåtña, largely untouched. Two nuclear weapons would achieve the same destruction as thousands of conventional missiles each with a payload in the 1000lbs TNT range.10

Such an attack could achieve enormous military benefits for China at relatively low risk of initiating a global nuclear war.11

A similar attack on Okinawa would be much more likely to trigger a US nuclear retaliation. Like Australia, Japan is a treaty partner and the population of the island is over 1m souls. Okinawa is also well within range of saturation attack by conventional Chinese missies (much more so than Guam), rendering the risk-reward calculus of using nukes unacceptable to Beijing, at least in the first instance - despite what the agitprop video at the masthead of this article might suggest.

Being a US state, Washington has no choice but to consider a lone nuclear strike on Hawaii on par with an attack on the homeland. This is why a blinding first strike on Oahu (home to Pearl Harbor, Hickam AFB, HQ USINDOPACOM, HQ and operational forces of US Marines and US Army) would likely take the form of a non-nuclear EMP and/or the severing of submarine cables, and other non-nuclear blinding actions.

No umbrella thank you, we’re British

France and the United Kingdom acquired nuclear weapons for a variety of reasons. WWII exhausted the old European powers. They were conscious of their weaknesses. It would be a mistake to assume they acquired nuclear weapons solely to deter Russia. As Churchill said, “There is only one thing worse than fighting with allies, and that is fighting without them”. After years of coalition warfare, they understood that Moscow was only one concern. Washington was also a real worry. They did not want to be pushed around by the new global power on the block that for centuries had remained in isolation (and thus experience). They wanted a seat at the table, they wanted to at least appear to be great powers, and especially in the case of the French, they were unwilling to imagine the US would trade New York for someone else’s attack on Paris.

The Europeans were sophisticated enough to realize that statecraft is all about interests not friendship. The Suez crisis of 1956 validated these concerns. Eisenhower undermined his old wartime comrades de Gaulle and Eden (with Churchill in the background).

So both pursued an independent nuclear deterrent and both achieved most of their objectives for doing so. As Kissinger remarked

“So long as strategic nuclear weapons were the principal element of Europe’s defense, the objective of European policy was primarily psychological: to oblige the United States to treat Europe as an extension of itself in case of an emergency.”

― Henry Kissinger, World Order: Reflections on the Character of Nations and the Course of History

So why would our closest allies in Asia, under a real and immediate threat, and after decades of American deterrence failures with US conventional power unable to keep pace with China, not adopt the same policy?

AUKUS SUBS - Ulterior motives?

AUKUS will make Australia the 7th nuclear submarine power in the world.12

Enormous emphasis has been placed by all three governments on the fact that Australia’s future SSNs will be nuclear powered but not armed.13

Currently, the announced sub plan is for Australia to lease 6-8 Virginia class SSNs between 2028 and 2040 during which time huge infrastructure investments will be made to start to manufacture a new UK designed SSN that is currently not even on a preliminary drawing board and that the Americans do not want. This plan requires Australia to operate and maintain two different SSN platforms. That is frankly ludicrous.

Thirdoffset has previously assessed that if Australia can gain access to the Virginias - a BIG IF - assuming the US Congress does deliver on IATR and related release of classified information and technologies, then the Virginia SSNs will almost certainly be the high watermark of AUKUS.14

Furthermore, the opportunity cost is ridiculous. Official Australian estimates put the costs of AUKUS at $368bn in 2023. Thats before the inevitable cost and time overruns for established programs (rule of thumb - double), let alone a “moon-shot” program like building nuclear subs from scratch in a country that does not even have nuclear power plants.

A brand new Virginia costs $4.3 billion. The current AUKUS budget of $368bn would buy 85 Virginia class subs. Of course a huge and complex infrastructure must be built. Excluding manufacturing boats, deep SSN maintenance and repair facilities will easily cost $100bn.15

The US should share this cost as it gains what would become the only protected maintenance facilities in the Pacific - the only other option - Guam - is a sitting duck. So accepting $100bn for facilities, that still comes out as 62 subs or 121 Arleigh Burke destroyers (currently $2.2bn). Unlike subs, Australia does have the shipyards, resources, skills and supply chains to build them (although not in those numbers). For comparison, the USN currently has 70 DDGs. The average cost of ahospitalin New South Wales is $50m that equates to AUKUS costing ~5360 hospitals.

For $368bn the alliance gets no additional hulls in the water. Australia is paying America to operate American subs that are coming off the production line with or without AUKUS.

Traditional military readiness rates run at about 1:3. That means Australia would only be able to put 1 boat to sea at any one point in time. Currently, Australia has just one Collins Class submarine ready for duty out of 6.

In Summary

Australia is going to spend $368bn on a moon-shot program that will likely double in price in order to be able to put 1 Virginia SSN to sea?

There is no way this makes sense. Or is there? Thirdoffset suspects that Australia has ulterior motives.

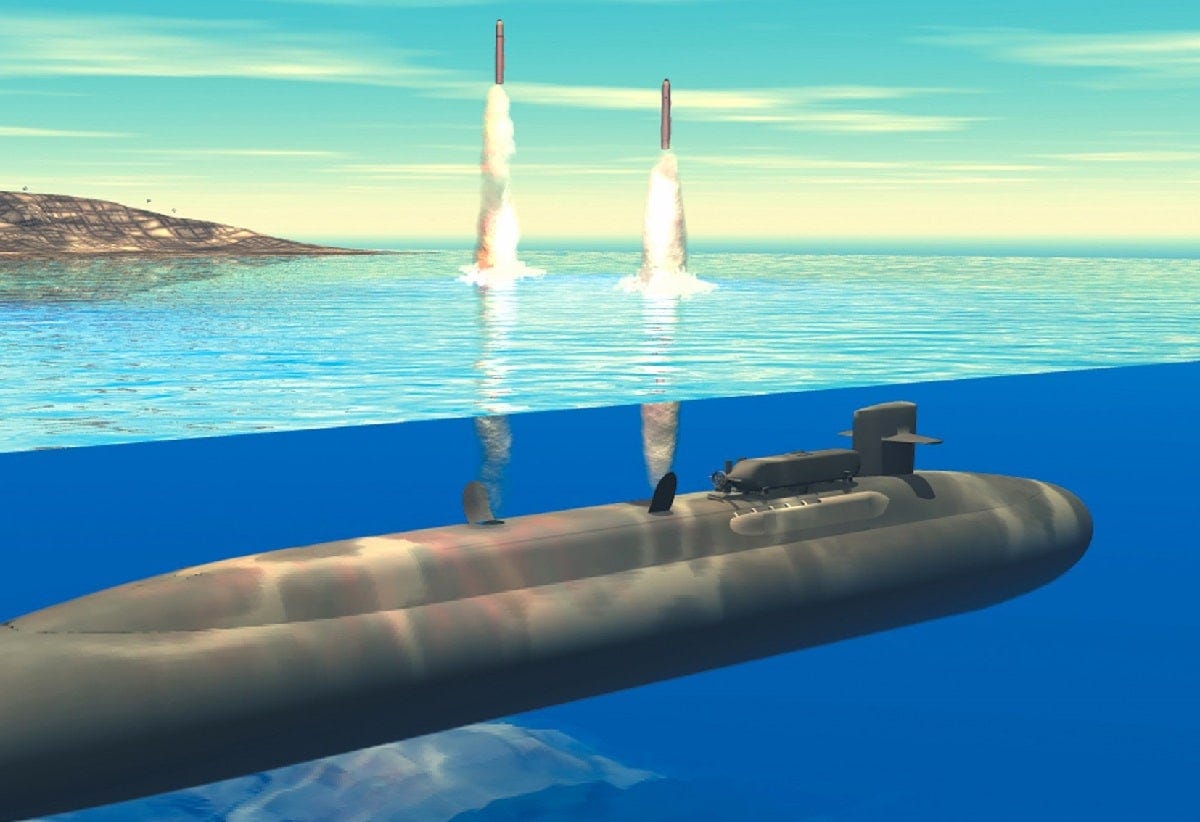

Tomahawk Sub Launched Cruise Missiles (SLCM) give a submarine its long range strike capability. Diesel and nuclear submarines can both accommodate tomahawks. However, there are critical operational reasons to select SSNs over conventional boats. Even the most advanced diesel boats must surface to breathe every other day. They also need to refuel their diesel tanks. These activities blow their stealth - particularly dangerous under conditions of ubiquitous ISR. Australian submarines have to travel great distances just to get to their area of operations. For example, Perth to Singapore is 2680 nm by sea through critical choke points like the Lombok strait and would take 11.2 days at 10 knots for a surface ship. That means they have to snorkel or surface around 6 times - not including refueling - an activity that depends on usage, but for arguments sake, might be once a month. Whereas the only limit on an SSN is food supplies. It can stay submerged on patrol for as long as the meat pies come out of the galley.16

An SSN is the only solution if you need to travel great distances, to stay on station undetected for the duration of a patrol, and have a good chance of survival in a shooting war against China. Recent war games by CSIS in Washington DC, have validated the unique characteristics of SSNs in a war with China inside the South China Sea, or what Thirdoffset likes to call “the Ring of Fire”. SSNs are not invulnerable, but hull for hull and payload on target, you can’t find a better platform.

SLCMs (Sub Launched Cruise Missiles - Tomahawks) provide a conventional long range strike capability deep inside the highly protected PLAs interior lines.17

Each SLCM has a 1000lbs (450kgs) warhead.

It has not been announced whether Australia will get new or used Virgina SSNs. If Thirdoffset’s suspicions are correct, at the very least, Australia should gain Block IV boats, if not Block V. Good arguments have been made by US shipbuilding experts that the USN needs to catch up on maintenance backlogs on existing boats, providing an additional window of opportunity for Canberra to snag the latest variants.

Block V boats will have a VPM module (Virginia Payload Module) with 4 silos that can each accommodate 7 Tomahawk cruise missiles. This would increase the total number from about 37 in Block IV to about 65.

In Summary

Given all of the above factors (in ideal conditions - Block V, only SLCMs loaded with no other missions, and optimal readiness/deployment rates), the entire Australian SSN force could generate one operational submarine with maximum 65 (1000lbs) warheads.18

By comparison a single B-52 can carry 20 Cruise Missies (ALCMs - same missile just air launched). The US has 33 B-52s ready to ‘fight tonight' capable of rapid delivery of 660 ALCMS.19

On top of these, there are B-1s, B-2s, US SSNs, SSGNs, and destroyers etc that would bring tomahawks to the fight.

The point of these ideal/notional back of the envelope comparisons is to ask whether the Australian SSN force brings anything critical to the fight for the price tag?

In coalition warfare, the subs would assist the US, but not provide a vitalcontribution. An additional 65 warheads never hurt, but in context of the volume of US fires, Australian SSNs would not be a game changer. In an anti submarine role an additional sub would add greater comparative value, yet it would still not have an impact on operations proportional to the program cost.20

If Australia is forced to go it alone, as its new defense strategic review suggests is possible, "the United States, is no longer the unipolar leader of the Indo-Pacific. Australia needs to develop the capability to unilaterally deter any state from offensive military action against Australian forces or territory”, then the SSN force makes more sense, particularly in an ASW role. Still, one Australian SSN up against 20 ready PLA-N subs (out of a total force of 56), let alone PLA-N ASW ships, would likely prove the adage that even with the best tech in the world, mass has its own advantages. And, as they say in tennis, advantage China.

SLCM-N

The Australians can only be serious about Virginia SSNs at that price point for one reason and one reason only. A stable and secure delivery system for nuclear weapons.

The only plausible reason Australia would spend nearly half a trillion dollars on a single military platform is to secure a future option for an independent nuclear deterrent. One sub on patrol with ~65 nuclear armed tomahawks, each carrying a 150kt warhead capable of flying under the radar for up to 1000m (2500km), is a total game changer. It provides Australia with a guaranteed “capability to unilaterally deter any state from offensive military action against Australian forces or territory”.

It is the only full guarantee of sovereignty. It imposes totally unacceptable risks to any aggressor under all possible conditions and scenarios. It will deter enemy coercion or punishment strategies because it delivers a virtually undetectable secure first and/or second strike capability.

Australia can not afford, nor can it man, an order of battle to meet the PLA ship for ship, plane for plane, missile for missile.

Even the US is struggling to keep up with the PLA. Secretary of the Navy Del Toro said that “China has 13 naval shipyards, with one of these facilities having more capacity than all seven US naval shipyards combined.” The Chief of Naval Operations said “The United States Navy is not going to be able to match the PLAN missile for missile,” Gilday said.

Marine Brigadier General Mark Clingan stressed that US "procurement is optimized for the 1990s and [the peace dividend] post cold war era. Our production may not be sufficient for future conflict"21

Chinese warship productions rates are hair-raising

Germany’s Vice Admiral Kay-Achim Schonbachsaid noted in 2021 that China’s navy is expanding by roughly the equivalent of the entire French navy every four years. Between 2017 and 2019, China reportedly built more vessels than India, Japan, Australia, France, and the United Kingdom combined.

In 2021, China commissioned at least 28 ships, while the U.S. Navy was positioned to commission seven ships that year. Should China continue to commission ships at a similar rate, it could have 425 battle force ships by 2030.

The story for merchant ship building is the same: “China built 44.2% of the world’s merchant fleet last year, followed by South Korea at 32.4% and Japan at 17.6% compared to only 0.053% by the US.”

America has already lost conventional military overmatch inside the first island chain. In fact, it may be at or below parity. In this context, extended deterrence looks like a paper tiger to its allies.

One SSN armed with SLCM-Ns offers Australia an unparalleled counter to the rapid expansion of PLA forces and any further intensification of aggression toward Australiafor its independent commercial and foreign policies.22

SLCM’s offer ambiguity in that they are duel use technologies. Until they arrive at their destination, the nature of the warhead is unknown. This further complicates the risk calculus of an enemy.

Additionally, the flight profile of an SLCM offers maximum flexibility in employment optionality. The disadvantage of ICBMs and SLBMs is they all follow a similar arc and signal an incoming nuclear strike inviting an immediate response before the first salvo lands. Additionally, the arc makes target identification between Russia or China indistinguishable until past reentry. SLCMs do not trigger an automatic counter strike.

Indeed, U.S. Strategic Command’s Admiral Charles Richard expressed the need for a wider menu of low-yield options before the Senate Armed Services Committee in May 2022: “What you want to be able to do is offer the President any number of ways at which he might be able to create an effect that will change the opponent’s decision calculus and get them to refrain or otherwise seek negotiation vice continued hostility.” He explicitly advocated for an SLCM-N to address the gap: “[A] low-yield, non-ballistic capability to deter and respond without visible generation is necessary to provide a persistent, survivable, regional capability to deter adversaries, assure allies, provide flexible options, as well as complement existing capabilities.” The Navy’s role in this new dispensation, therefore, is to ensure a survivable deterrent, to multiply a U.S. president’s options, and to shore up a willingness to wage war against a nuclear-armed opponent. But only if the fate of the SLCM-N program is reconsidered in this context.

Consider this scenario:

Assuming 3 SLCMs made it to Yumen undetected, they would be sufficient to serious degrade the Chinese ICBM silos - as seen below. There are a number of reasons why this would be a highly unlikely use of the weapon, but in extremis, if Australia’s objective was to make a show of force attack in a remote location with little to no collateral damage, this would be an option. However, due to these silos being a deception program/missile sponge, any attack here would be more a warning/ demonstration shot than of high operational utility.23

Obstacles

Critics of the SLCM-N idea for Australia will rightly point to various treaties, the requirement of the US to build and sell the system - which has been a matter of controversy going back and forth between democratic and republican administrations - and a variety of other challenges, including Australian C2, transport, storage, basing, and all manner of other issues. America may not want Australia to have a system the US cannot control. An American audience might also confuse New Zeland’s anti nuclear stance with Australia. The latter understand and accept NZ’s position, but Australia has always seen things a bit differently.

These are all important and valid concerns.

But they miss the point. If a country feels sufficiently threatened and it has no other effective option available, it will do things that surprise people. As previously noted, the new Australian strategic review demonstrates a seriously heightened state of Australian sensitivity to the threat and it assesses American unreliability might force Australia to go it alone. The same document that also states how much closer Australia wants to get to the US. This is not a contradiction. They need the technology more now because they are concerned about American unreliability later. It is also a warning from the junior to senior partner that what they have been saying behind closed doors is now important enough to raise publicly in official documents.

At some point in the future, under certain conditions as yet unknown, it may suit American deterrence policy to have a nuclear armed Australia (Japan and/or South Korea) posing an additional risk calculus on Beijing. Britain and France are becoming more engaged in the Indopacific but they are unlikely to risk their sovereignty in a nuclear shooting war on the other side of the world.24

If Australia’s back really is up against the wall - and it can not afford to build and maintain a conventional force of the size, scale and capacity needed to force China to never consider coering Australia something it has done with some regularity of late) - Australia will need a nuclear deterrent.Thirdoffsetsuspects Australian strategic planners know this and have selected the SSNs in order to give them future options.

In secret nuclear talks, the Australia government has already told the US that it wants its own nuclear weapons

The Australian Prime Minister told the US Secretary of State that

he didn't trust the Americans to keep their side of the treaty that underpinned Australia's security. He could not rely on US protection in the event of a nuclear attack. And he wanted the option of developing Australia's own nuclear bomb.”

In response, America sent a review panel to Australia to evaluate their weapons building capabilities.

The US experts were "particularly impressed" by the independence of Australian officials [and had] "confidence [in] their ability to manufacture a nuclear weapon and desire to be in a position to do so on very short notice".

The year was 1968. The Prime Minister was WWII RAAF veteran John Gorton and the Secretary of State was Dean Rusk.

Few will know that by then, Australia has already suffered multiple nuclear strikes, had already been co-responsible for command and control of nuclear weapons, and avidly pursued a full nuclear weapons program for many years.

The father of AUKUS was known simply as “the Joint Project”.25

It was an Anglo-Australian agreement for cooperation on nuclear power and weapons development. In exchange for access to nuclear technology, Australia would allow the British to conducted 12 nuclear tests on Australian soil (ca. Hiroshima bomb size). This was later superseded by an Anglo-American agreement that cut Australia out. So Australia continued itsown plansthat became very well advanced and included the purchase of the F-111 bomber and other nuclear warfare infrastructure.

If you have wondered why Britain was involved in AUKUS, this might be the start of a serious explanation. In theory, AUKUS makes sense for Britain to try and get its first post-Brexit sale of a major product. But as previously noted, it is next to impossible that a British sub will be built in Australia. The UK know that. Perhaps Australia will use AUKUS to finally get properly compensated by the UK (and/or US) for the abandonment of the Joint Project? Or to balance the UK against the US if the latter is not inclined to share weapons technology at some future point of acute need?26

What is certain is that without SSNs, Australia would have no viable way to securely employ a nuclear weapon against China. With SSNs and SLCMs, it has options. That is worth the price tag. Australia also has an extensive and serious track record of pursuit of nuclear weapons. Its commitment was such that it exposed its officials and indigenous people and a portion of its sovereign territory to 25,000 years of plutonium half life poisoning in order to have a future option on an independent nuclear deterrent. That option is alive and well in 2023 and maybe more likely to be realized with the active assistance of its nuclear allies than ever before. Certainly the inclusion of the nuclear option explains the otherwise inexplicable elements of the AUKUS deal (British involvement, extreme cost, convoluted multi-platform acquisition and so forth).

Japan and South Korea

Australia has not been the only Indopacific power thinking about back stopping its defense with nuclear deterrence in light of Chinas aggression and creeping American isolationism.

Trump’s alliance-bashing has planted new seeds of doubt, this time about the reliability of America’s alliance commitments writ large. In other words, allies’ confidence in extended deterrence has been battered from all sides.

The results speak for themselves. Having been the only victim of a nuclear attack and having been occupied by American forces that wrote the pacifist Japanese constitution prohibiting Japan from having armed forces - Japan’s reluctance to alter this long standing status quo has been subtly shifting for about a decade now. The Quad was the brain child of the late Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe. He assiduously cultivated the alliance-hating, mercurial Trump, because Abe could not afford to allow Trump to suddenly withdraw all US forces from the region - an order Trump nevertheless gave in the lame duck period after the 2020 election that was simply impossible to execute before the inauguration.

Just as the Australians had identified the twin threats of an increasingly aggressive China and a fear of an unreliable America, Japan has reached a threshold where it has decided to place its national security ahead of historical strictures and diplomatic gestures that go no where.

Japan has a technologically advanced and highly capable self defense force. Its capabilities have been very carefully restricted to defensive roles in accordance with its constitution. It does not have any long range power projection capabilities. For years now they have had to scramble their fighters, coast guard, and navy, to answer daily PLA incursions into their sovereign territory. They have weathered scores of ballistic missile “tests” from North Korea whose missiles have fallen all around the home islands - to include flight paths clear across Japan. Many times alarms have sounded sending civilians rushing to shelters unsure if the incoming missile will land long or short or “accidentally” strike a city. This has added an unnecessary sense of instability to a country that is no threat to anyone. More recently, the surge of the Russian pacific fleet into the waters around Japan in coordination with the PLA has created such a sense of menace that the patient, studied, and measured Japanese have decided that they are no longer going to tolerate.

Japan just doubled its defense budget and challenged some of its constitutional restrictions by deciding to acquiring long range fires in order to deter its overtly aggressive neighbors. It’s has assertively put a lot of energy behind not just the US alliance but also the Quad, and intensified its focus on a wide range of important bilateral relationships. Thirdsoffset noted a truly stunning development last December when Japanese fighter aircraft landed in the Philippines for the first time since WWII on the anniversary of the battle of the Philippines. This was a truly stunning decision on behalf of both countries and a spectacular act of reconciliation and future partnership.

The region is heavy with history. It continues to have important lessons for us all. Those lessons are being put to work in forging these new relationships designed to resist autocratic threats, hybrid warfare and growing outright aggression. In the 1930s those impulses came from Tokyo. A new, rapidly growing power, Japan was filled with nationalist pride and was willing to throw its weight around to get its way. It had to learn the hard way that international relations offers no benefit to aggressors. At least in the long term. Beijing is the historical analogue and it is making all the same mistakes. Today, sober, mature, sophisticated, confident, and deeply democratic and peaceful; Japan is fully integrating with its democratic neighbors to resist the new hot-headed regional hegemon eager to bully its way in the world for no discernible good purpose other than power politics and impatient vengeance.

Understandably, Japan’s greatest taboo is nuclear weapons. It is a sign of the seriousness of the threat that Japan has started to take some steps - imperceptible to outsiders perhaps, but momentous to the Japanese - in relationship to the nuclear issue.

Breaking defense noted back in November 2022 that

Japan’s ambassador to Australia, Amb. Shingo Yamagami, told the conference his nation was prepared to host Australia’s future nuclear submarines and wants to participate in the AUKUS alliance on “specific projects.”

“Japan stands ready to discuss with Australia, the US and the UK areas where we can co-operate bilaterally on defence technology,” he said.

This is not a one-off event. In a remarkable op-ed in Nikkei Asia just recently it was reported that

In February, “a Japanese defense study group chaired by Ryoichi Oriki, a former military chief of staff, suggested Japan ease its three nonnuclear principles that prohibit possessing, producing or allowing entry into Japan of nuclear weapons.”

Thirdoffset’s network in Japan reports that Japanese officials keep quiet on the nuclear options ‘on the surface’. Like South Korea, and more than Australia (that does not have nuclear power reactors), Japan has the technical capability to develop nuclear weapons in very short order.

It may be South Korea that leads the way in developing its own nuclear deterrent. Incredibly, “some polls in South Korea show about 70% popular support for acquiring nuclear weapons.

A strategic analyst at South Korea's defense ministry cautioned the US that "If the U.S. hesitates to retaliate [against a Russian tactical nuke in the Ukraine war] with nuclear weapons, North Korea might think it could use nukes," he said. "If so, arguments for possessing nukes will further gain momentum in South Korea.”

As a consequence, at a White House meeting with President Yoon, on April 26, the US announced that it would enhance its extended deterrence to protect South Korea by establishing a joint nuclear planning and decision-making unit with South Korea. This appears to have satisfied the South Koreans. For now.

The real headline was that a defense ministry official was willing to go on the record to stress to America (and no doubt China) that there is already “momentum” for an independent deterrent. In polite diplomatic circles, that is a step further than the Australians warning the US Australia is prepared to go it alone if needed.

Conclusion

Hemingway wrote that bad things tend to come ‘gradually, then suddenly’. Americas conventional deterrence failures of the past twenty years have now cascaded into a deep erosion of extended deterrence. Never fully credible, the erosion has been exacerbated by the loss of US conventional overmatch against China in the ring of fire (South China Sea). For the first time in history since 1945, US forces are now facing the prospect of having to “fight to get to the fight”. The access the US enjoys to Ukraine will not exist in the Taiwan scenario, not just because Taiwan is an island but because the US will be directly fighting a nuclear power (something it refuses to do in Ukraine), 100 miles off a coast that is bristling with thousands of missiles, fighters, ships and subs, all ready to deny clear skies and following seas to US forces.

The CNO (and many others) openly admit the US can not match the PLA ship for ship or missile for missile. He also admitted that the long standing policy of being able to fight two regional wars at once is not viable. The US spends more on defense than the next 9 countries combined. If the US is already lagging - what hope is there for smaller powers that cannot afford a massive conventional military like Americas?

The only guaranteed sovereign option for existential deterrence is a nuclear weapon that can be assured to reach its target. Just one Virginia Block V SSNs with 65 SLCM-Ns sitting undetected off the Chinese coast will prevent China from touching Australian interests. Australia almost realized a major nuclear weapons program in the past. It will adopt one again if circumstances demand. So will South Korea. So will Japan. If China continues along Xis impatient, bellicose, and hyper nationalistic path, that has pushed the entire region into the arms of America, it will one day be confronted by not just one nuclear power, but three or four, vastly complicating its strategic options.

Thanks for reading The Third Offset Strategy! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

A little nuclear proliferation light relief

Some would say there were other reasons why the British obtained their own deterrent

Finally Tom Lehrer explains proliferation in under 3 mins